On August 31, the book Whistling Under the Snow (ed. Adrián Soto, 2023) was presented at the main public library of Helsinki, Oodi. The 288-page book and two large blocks of photographs, is a narrative exercise between recent history and journalism.

The rich testimonies of the protagonists also represent a rescue of memory. The book offers a background to the events of 1973, in both Chile and Finland. During a peak period of the Cold War, Finland opened its doors, for the first time in its history, to a small number of refugees from Chile. Now, half a century later, these refugees tell their personal story that is also collective.

Photo © Luis Bustamante.

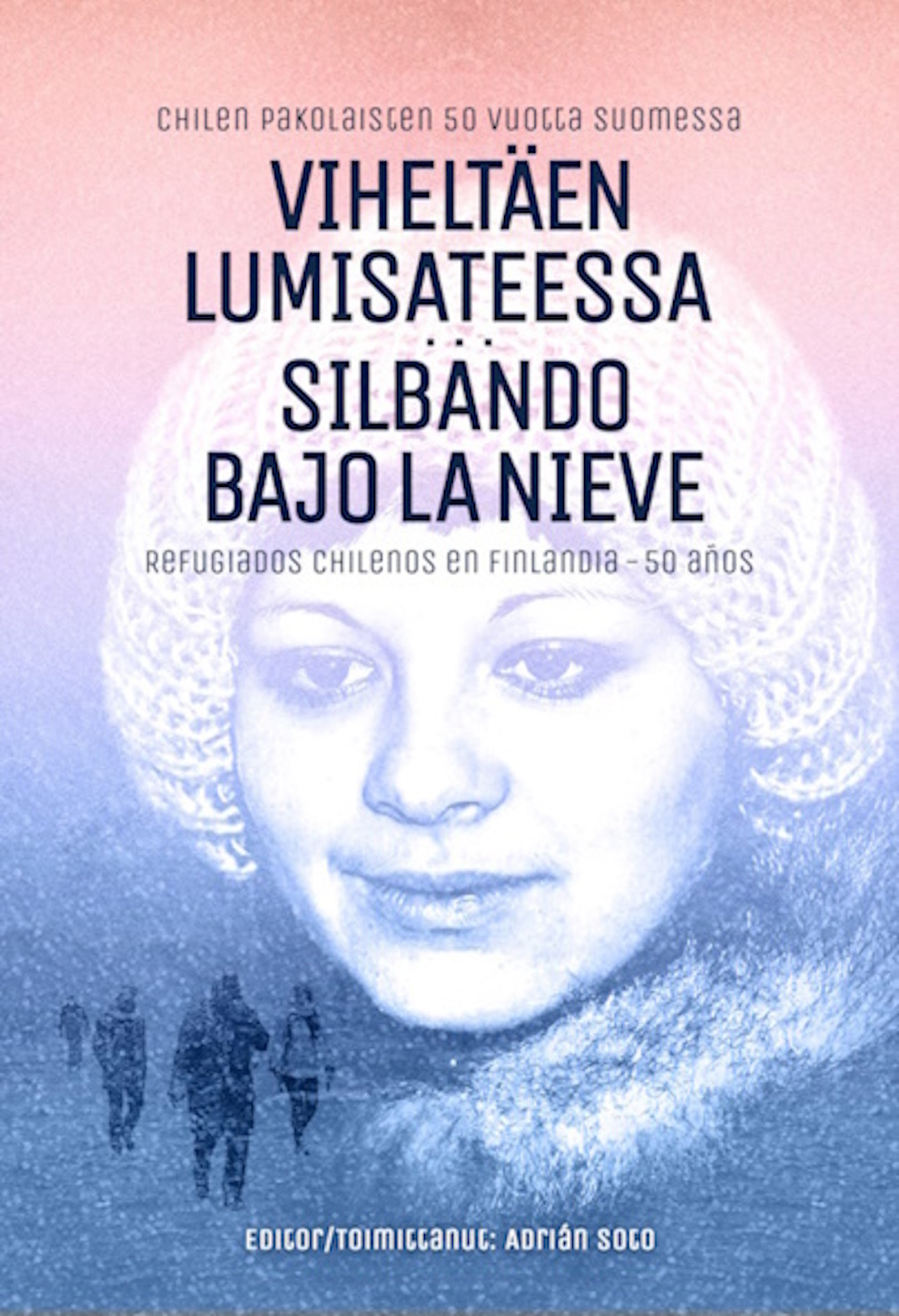

The book is bilingual, Finnish and Spanish and its name in Finnish is Viheltäen lumisateessa and Spanish is Silbando bajo la nieve.

The following text is the presentation made by the editor, Adrián Soto, before the members of the Association of Spanish Teachers of Finland, in Helsinki, December 2, 2023

Many essayists and columnists advise us that we should go to the Greek classics to seek answers to the ills of modern society. I would like to start there. The first playwright of Classical Greece, Aeschylus, in the 5th century BC, upon being expelled from Athens, asked the question:

Can an strange land become our homeland?

The answer from us, Chilean refugees who arrived in Finland in the seventies, is Yes, it is possible, but the process is long and difficult.

The tragic events in Chile in September 1973 led the Finnish government at the time, headed by Prime Minister Kalevi Sorsa, to accept one hundred refugees from Chile. Such a decision had significant importance in the recent history of Finland. From that moment on, policies towards refugees and later also immigration policies began to be forged and regulated.

Two years ago I received the task of editing the book about the Chilean exile in Finland. My first task was to carry out a search of secondary sources, that is, published literature. I must say that in addition to a couple of degree theses there are two publications that indirectly deal with the topic: The book Kuoleman Lista by Professor Heikki Hiilamo published in 2010 which deals with the work of the diplomat Tapani Brotherus in Chile after the military coup, and in which The television series Invisible Heroes is based, which premiered in April 2019.

In 2021, journalist Pirjo Houni published Salatu diplomattiaa, which is a biography of Tapani Brotherus and his long diplomatic career.

Nor have the ethnic groups settled in Finland published much, with the exception of the book Suomen tataarit (the Tatars of Finland), which recounts the 150 years since the arrival of this group to Finland, constituting the first Islamic community in the country. The book is the work of researcher Antero Leitzinger.

I told my compatriots that we should not wait 150 years to tell our story. What 50 years is enough for us!

Works on several archives

After searching for secondary sources I went to the primary sources. For that, I did research work in the Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Relations, in the archive of the Red Cross and in the Archive of Kalevi Sorsa. I also reviewed the newspaper archive of the time. From these investigations, article 2 of the book was born entitled: This is how the decision to receive refugees from Chile was made.

Finland knocked on many European doors, as it was organizing the great conference on Security and Cooperation (Etyk) that was finally held in 1975. In all European capitals the events in Chile had had a great impact. On October 23, 1973, Antti Lassila, division head of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, wrote a memorandum in which he proposed to the government to receive 30-40 refugees from Chile. In that memorandum Lassila stressed that a week earlier Switzerland had decided to receive 200 refugees from Chile. Switzerland was always an exception in Europe for not receiving refugees. On October 24, the Government of Kalevi Sorsa made the decision to receive one hundred refugees from Chile.

In Finland, to manage the arrival of refugees, two Special Commissions (Pakolaiskomissiot) were formed, the first was led by the Finnish Red Cross and the second by the Ministry of Labor.

The initial number of one hundred refugees was increased to 150 in 1976. The following year in 1977, Chile’s refugee program ended, whose number had increased by 182. By that same time, Sweden had received 2,648 refugees and France 2,021. The total cost of this operation to the Finnish public treasury was 2.5 million markaa, or about 400,000 euros.

In the seventies and eighties, a handful of Chileans arrived and, with the pain of broken dreams, began to forge new lives in these Nordic lands.

As exiles we have had to compose our lives through memory. Many of us have lived outside of real time, like living ghosts, with a suitcase ready for our return. Today the first refugees are all older people, so soon we will be gone. That is why we consider rescuing our memory.

But the exercise of rescuing memory is not easy. The exact time on calendars does not always agree with memory. Furthermore, the time of the exile clock has its own rhythm and its hands do not always move forward. It is an eternal battle against mirages.

We belong to a generation that dreamed of social reforms, but in response we received lead and savage repression. This included the loss of the country where our cultural roots were. Added to that was the loss of the utopia where our ideals were placed. All these elements are part of a bitter cocktail that Chilean refugees have had to drink from. These reflections can be found on page 87 of the book.

The book is divided into three well-defined parts, the first describes the background of the repressive policies in Chile and the dilemma of Finland’s decision to welcome refugees. In a second part, the life course of four refugees is described, two women and two men, who managed to develop their lives in very different work activities. in a cultural environment very different from what Chile could offer them.

In a third part is the cultural contribution of Chileans to the cultural media of Finland. We have the work of renowned artists, the 30 years of work of the Gabriela Mistral Children’s Club and the work of a good number of musicians. We can say that Latin American music also arrived with us, and that today, it is already part of the musical landscape of Finland.

The entire theme of the book is, from a graphic point of view, well documented. It contains two large blocks of photographs, one black and white for the period of the seventies and eighties; and a block of color photographs to document more recent times. Let me tell you that: being a bilingual book, Spanish-Finnish, it is, for you, an ideal work tool. The book contains 288 pages of which 60% are in Spanish and 40% in Finnish.

The book is well documented with photographs

The Pinochet dictatorship in Chile was tragically long-lived and installed a draconian economic model, an extreme neoliberalism, which still persists today, after 30 years of democratic regimes. The levels of inequality in Chile are simply scandalous. 1% of the population receives 29% of the national wealth annually.

Both cover of the book, designed by Kati Vera

Of the 182 Chileans who arrived as refugees, about 50 remained in Finland. A good number returned to Chile at the end of the dictatorship. In those 17 years of dictatorship, other refugees had formed Finnish families and return was no longer a simple thing. Later, as the years go by, the refugees also age. At 55 or 60 years old it is very difficult to start a new life in a country like Chile where 65% of the population is under 35 years old. As the years went by, the reality of the country also became blurred.

The motto or nickname of Whistling Under the Snow is a narrative exercise between recent history and journalism. At the time of our arrival, Finland was undergoing notable structural changes: It must be said that Finland in the seventies was politically and culturally speaking very different from the Finland we have today. This topic is well elaborated from page 42 onward.

The solidarity movement with Chile was transversal where all the living forces of society participated. And it lasted a whole decade. Afterwards, an attempt was made to emulate it, without results. The movement marked an entire generation of Finns and Chileans. The newspaper archive is very rich in testimonies.

The first months of our stay in Finland were marked by obvious uncertainty. The country was not prepared to receive us, and most of us had no real idea of where we were. The officials of the Red Cross and the Ministry of Labor improvised one day and the next as well. At the end of its activities in 1977, the second Special Commission became self-critical and regretted not having attended to the psychological and emotional side of the Chilean refugees. Several of the refugees arrived directly from the torture centers.

Another of the Commission’s recommendations was to teach mother tongue to school-age children. With the education of their native language, the child strengthens their self-esteem and will be better prepared for school life. This recommendation reached Parliament and a law was legislated in 1979, but at the beginning there were no Spanish teachers. From that moment on, the Gabriela Mistral Children’s Club was born to strengthen children’s Spanish and instruct them in Latin American culture. See page 150.

In 1972 Finland legislated a new and successful school law. 21 refugee children joined the classrooms. All the children who remained in Finland successfully completed the basic cycles of Finnish school. These boys and girls are currently 55-60 years old and are integrated into Finnish society. See page 37.

The Finnish authorities obtained valuable experiences with the Chilean refugees that could soon be put into practice with the arrival of the Vietnamese refugees at the end of the seventies. These teachings were also useful with the arrival of Somali refugees after the fall of the Soviet Union and of Kosovo Albanians in 1992, who arrived through international commitments.

Integration policies had to wait a long time. The first comprehensive law (kotouttamislaki) was only enacted in 1999, 25 years after our arrival. And the first law instructing municipalities to manage the arrival of foreigners was enacted in 1995 (kotikuntalakia 201/1994) twenty years after our arrival.